Transforming a Schoolyard: Our Citizen-Led Street Experiment

By: Marco te Brömmelstroet and Sjoerd Brandsma

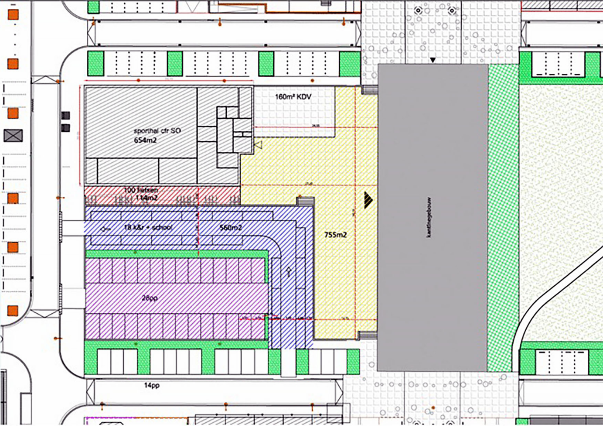

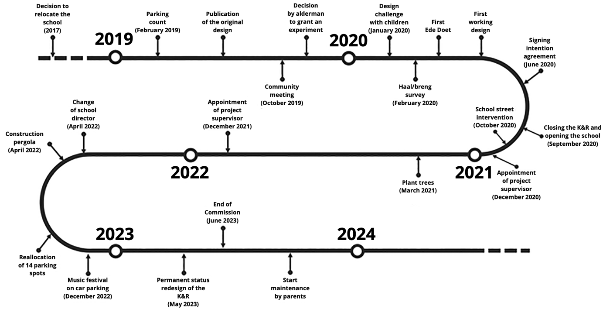

When the city of Ede announced plans in 2018 for a new elementary school in the ENKA neighbourhood, we were excited — and concerned. The plans, designed by leading urban planners and architects, followed every regulation, norm, and guideline. Every square meter had a dedicated purpose, from playground space to car drop-offs. On paper, it was perfect. In practice, it left almost no room for greenery, play, or social life. The schoolyard would be a hot, paved space with minimal connection to nature, while the large parking and drop-off zones dominated the site.

As local residents and parents, we felt compelled to act. From 2018 to 2024, we joined a citizen-led design team to challenge not only the schoolyard’s layout but also the rigid, norm-driven design process itself. We wanted a school environment that was both physically resilient — providing green, diverse, and healthy play spaces — and socially resilient, fostering connections between children, parents, teachers, and neighbours. In this recent article, we share our experience.

Listening to the Community

Our first step was simple but powerful: we listened. Together with an external agency, we documented the visions of children, parents, teachers, and neighbours. During a design festival, one message was clear — everyone wanted a much greener schoolyard.

Meeting this vision meant tackling a big challenge. The playground itself was too small, and the soil was polluted. To create space and healthy ground, we had to rethink the 1,100 m² car park and drop-off zone. Using a community survey, we gained the confidence of the Deputy Mayor for Mobility to allow a two-year experimental transformation, temporarily converting part of the parking area into green space for children to play and neighbours to socialize.

How We Made It Happen

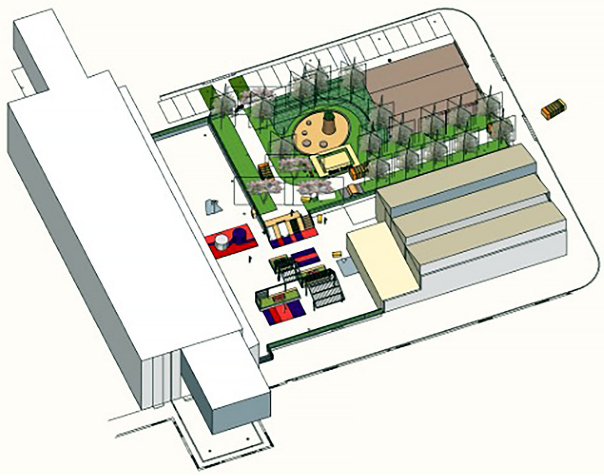

From the start, the experiment demanded radical change. For several weeks, we closed the schoolyard to car traffic, encouraging children to walk or cycle independently. Together with families, we transformed the drop-off zone into a temporary playscape — adding healthy soil, planting trees, installing picnic tables, creating sandboxes, and stepping stones. Eleven cherry trees were planted strategically to create a visually green and inviting space, while temporary infrastructure allowed soil, water, birds, and insects to thrive.

At the same time, we had to ensure feasibility. Funding came from municipal grants and community contributions — including €16,000 raised by children through neighbourhood vouchers. We engaged municipal stakeholders, project developers, and school users to maintain support and navigate tensions between opposing neighbours and institutional stakeholders.

Communicating and Mobilizing the Community

Communication was essential. We used newsletters, information boards, social media, and direct conversations to keep everyone updated. Children were active participants, building bird nests, adopting trees, and helping maintain the garden. Volunteers acted as traffic guards, helping parents understand the new pick-up and drop-off routines. Crowdfunding and surveys not only raised money but increased awareness and ownership among parents and neighbours.

The transformation itself became a communicative tool, showing that a greener, more active streetscape is possible. Visitors, councillors, and even school directors from other areas came to see the experiment, helping inspire broader conversations about sustainable, child-friendly urban spaces.

Facing Challenges

Not everything went smoothly. The school grew from 250 to over 450 children, childcare facilities doubled in size, and ongoing construction required constant adjustments to parking and traffic routes. Institutional support was limited; the municipality and school often deferred responsibility for long-term enforcement, leaving the volunteers to navigate conflicts and maintain progress.

Despite these challenges, the experiment highlighted the power of citizen-led action. We learned that radical change is possible, but sustaining it requires both community engagement and active support from institutional stakeholders.

Evaluating the Impact

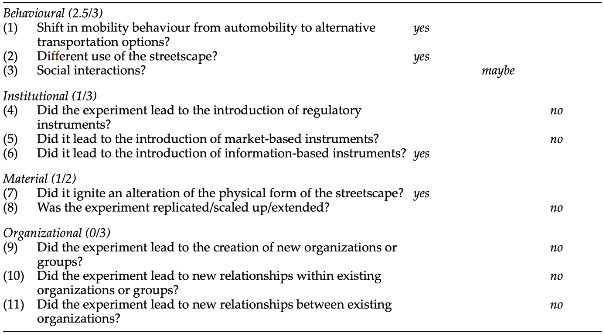

We assessed the experiment across four dimensions:

Behavioural change: Most children now walk or cycle to school independently. Bike racks filled quickly, and car traffic decreased compared to other schools. The experiment also fostered social connections, with children playing more, teachers and neighbours using benches, and everyone engaging with the new natural environment.

Institutional change: Results were mixed. The municipality referenced our experiment in mobility policy, but new schools still followed traditional, car-focused designs. The school and daycare encouraged walking and cycling but took limited ownership of drop-off enforcement, leaving some parents unaware of the unique process behind the changes.

Material change: The 560 m² drop-off zone became a multifunctional green space with trees, plants, water infiltration, play equipment, and biodiversity. Half of the former parking area is now used for play and bike storage, while the other half remains underutilized for cars.

Organizational change: Our volunteer group drove the project from start to finish but disbanded afterward. No other stakeholder fully took over, meaning enforcement and long-term maintenance remain uncertain.

Lessons Learned

Citizen-led experiments can create real change, but they have limits. Physical transformation without organizational ownership can leave communities in limbo. Success depends on “institutional entrepreneurs” — motivated individuals within organizations who can open space for citizen initiatives. Sharing dreams, not just problems, helps activate these key players.

Participation comes with risks. Balancing radical ideas with feasible actions is stressful, and volunteers need protection from conflicts with existing policies or local opposition. Strong stakeholder support is essential, even when opposition comes from a small minority.

For school environments, time matters. A four-year development period may seem long for urban planners, but it’s half a child’s school life. Children must have a voice in the design process, and their needs must be central.

Systemic change requires more than physical redesign. To truly transform spaces, we must challenge the norm-driven, technocratic mindset that governs current urban design. As Pirsig said, “if a factory is torn down but the rationality which produced it is left standing, then that rationality will simply produce another factory.” To create resilient streets and schoolyards, we must change the underlying assumptions, values, and ways of working that shape our cities.

Final Thoughts

Our experience showed that citizen-led street experiments can transform not only physical spaces but also the social life of neighbourhoods. They teach us the power of community, the importance of listening to children, and the need to challenge rigid norms. But long-term success requires supportive institutions, committed stakeholders, and ongoing engagement.

We hope our story inspires others to imagine what’s possible when citizens, institutions, and children work together to reclaim streets for people — not just cars.

Source: Te Brömmelstroet, M., & Brandsma, S. (2025). From Citizen-Led Street Experiments to Transformative Change: A Case Study in Improving School Environments in the Netherlands. Built Environment, 51(3), 436-457.

https://www.ingentaconnect.com/contentone/alex/benv/2025/00000051/00000003/art00008

Podcast: the cherry tree revolution

Listen to the story as a podcast. Created with Wondercraft.ai